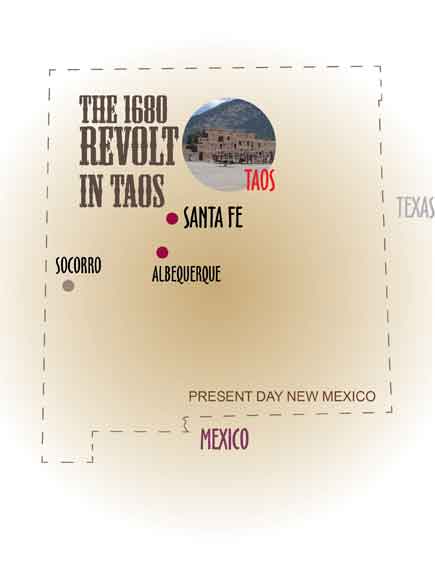

BELOW is a brief look at the Pueblo culture in Taos (present day New Mexico) and the revolt that started in 1680.

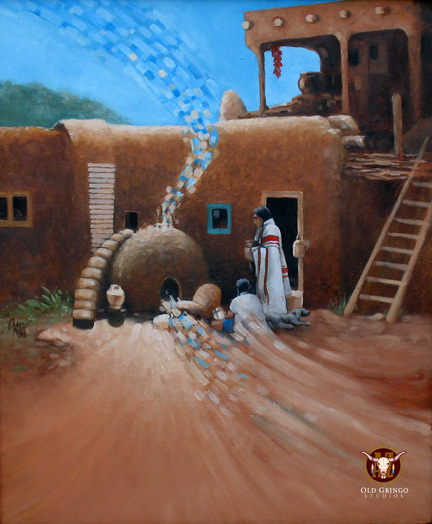

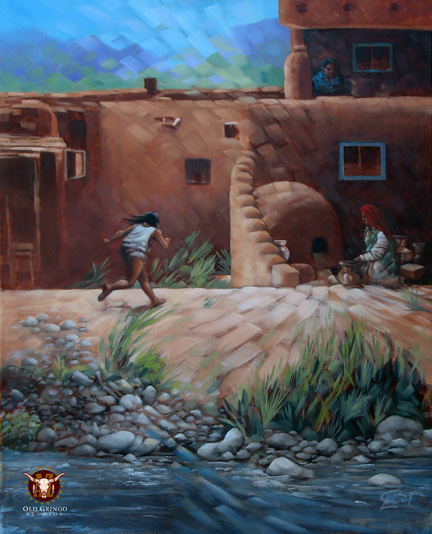

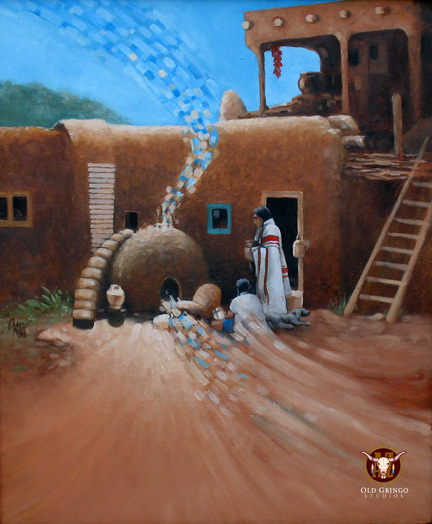

The HORNO (silent “H”) was central to life in the Pueblo culture. Wood was burned inside this brick and adobe oven to heat it. The wood

was then removed and the oven ready to use.

This illustration by the author shows the connection -- Earth, Wind and Fire.

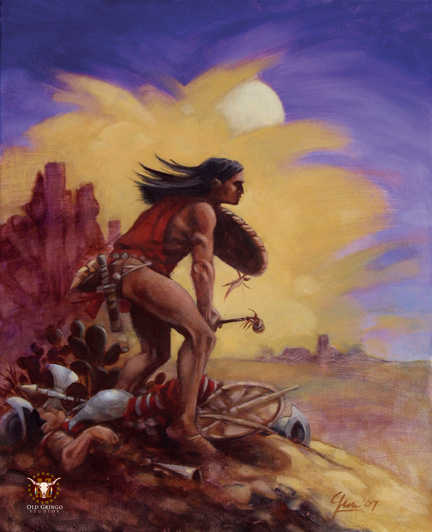

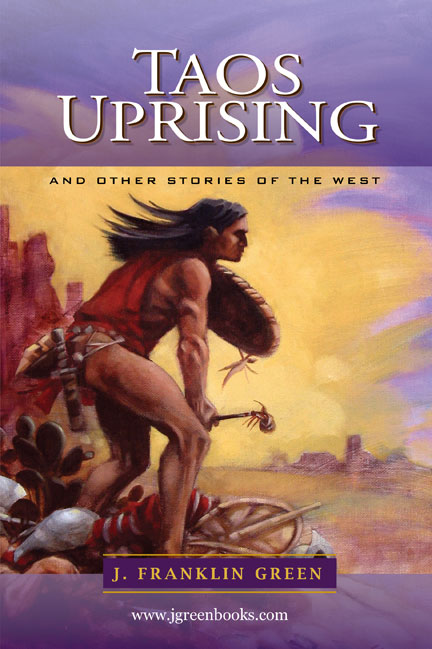

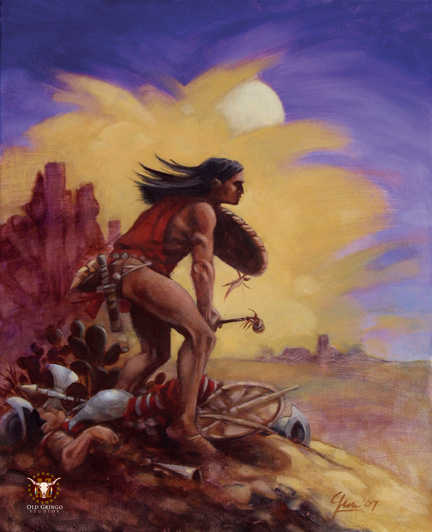

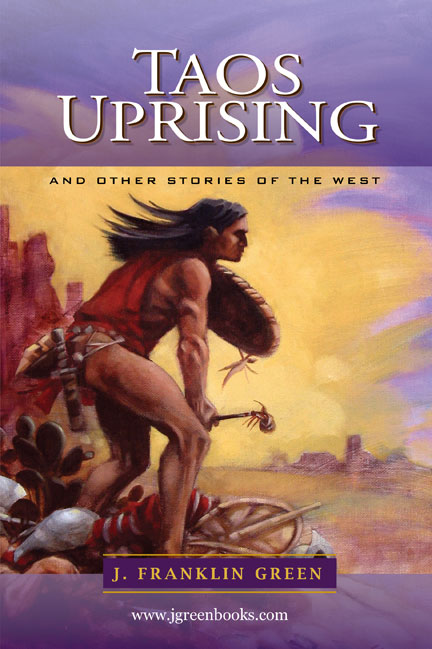

This painting done by the author in 2007 depicts one small scene from the revolt and eventually became a book cover in 2018.

----------------------------------------------------

The Puebloans or Pueblo peoples, are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material and religious practices. When Spaniards entered the area beginning in the 16th century, they came across complex, multi-story villages built of adobe, stone and other local materials, which they called pueblos, or villages, a term that later came to refer also to the peoples who live in these villages.

There are currently 100 Pueblos that are still inhabited, among which Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi are the best-known. Pueblo communities are located in the present-day states of New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas, mostly along the Rio Grande and Colorado rivers and their tributaries. The term Anasazi is sometimes used to refer to Pueblo people but it is now largely dispreferred. Anasazi is a Navajo word that means Ancient Ones or Ancient Enemy, hence Pueblo peoples' rejection of it.

Puebloans speak languages from four different language families, and each Pueblo is further divided culturally by kinship systems and agricultural practices, although all cultivate varieties of maize.

Despite increasing pressure from Spanish and later Anglo-American forces, Pueblo nations have maintained much of their traditional cultures, which center around agricultural practices, a tight-knit community revolving around family clans and respect for tradition. Puebloans have been remarkably adept at preserving their core religious beliefs all the while developing a syncretic approach to Catholicism. In the 21st century, some 35,000 Pueblo are estimated to live in New Mexico and Arizona.

-----------------------------------------------------

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE REVOLT.

The below, extracted from several annotated sources is the history or at least as much as known of the Taos/Pueblo uprising. NOTE – Two different spellings are used below – Popé as used in the story and Po’pay.

The primary cause of the Pueblo Revolt was probably the attempt by the Spanish to destroy the religion of the Puebloans, banning traditional dances and religious icons such as these kachina dolls.

-------------------------------------------------------

In November 1681, Antonio de Otermin attempted to return to New Mexico. He assembled a force of 146 Spanish and an equal number of Indian soldiers in El Paso and marched north along the Rio Grande. He first encountered the Piro pueblos, which had been abandoned and their churches destroyed. At Isleta pueblo he fought a brief battle with the inhabitants and then accepted their surrender. Staying in Isleta, he dispatched a company of soldiers and Indians to establish Spanish authority. The Puebloans feigned surrender while gathering a large force to oppose Otermin. With the threat of a Puebloan attack growing, on January 1, 1682 Otermin decided to return to El Paso, burning pueblos and taking the people of Isleta with him. The first Spanish attempt to regain control of New Mexico had failed.

Some of the Isleta later returned to New Mexico, but others remained in El Paso, living in the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo. The Piro also moved to El Paso to live among the Spaniards, eventually forming part of the Piro, Manso, and Tiwa tribe.

The Spanish were never able to re-convince some Puebloans to join Santa Fe de Nuevo México, and the Spanish often returned seeking peace instead of reconquest. For example, the Hopi remained free of any Spanish attempt at reconquest; though they did, at several non-violent attempts, try for unsuccessful peace treaties and unsuccessful trade agreements.For some Puebloans, the Revolt was a success in its objective to drive away European influence.

RECONQUEST

The Spanish return to New Mexico was prompted by their fears of French advances into the Mississippi valley and their desire to create a defensive frontier against the increasingly aggressive nomadic Indians on their northern borders. In August 1692, Diego de Vargas marched to Santa Fe unopposed along with a converted Zia war captain, Bartolomé de Ojeda. De Vargas, with only sixty soldiers, one hundred Indian auxiliaries, seven cannons (which he used as leverage against the Pueblo inside Santa Fe), and one Franciscan priest, arrived at Santa Fe on September 13. He promised the 1,000 Pueblo people assembled there clemency and protection if they would swear allegiance to the King of Spain and return to the Christian faith. After a while, the Pueblo rejected the Spaniards. After much persuading, the Spanish finally made the Pueblo agree to peace. On September 14, 1692, de Vargas proclaimed a formal act of repossession. It was the thirteenth town he had reconquered for God and King in this manner, he wrote jubilantly to the Conde de Galve, viceroy of New Spain. During the next month de Vargas visited other Pueblos and accepted their acquiescence to Spanish rule.

Though the 1692 agreement to peace was bloodless, in the years that followed de Vargas maintained increasingly severe control over the increasingly defiant Pueblo. De Vargas returned to Mexico and gathered together about 800 people, including 100 soldiers, and returned to Santa Fe in December 1693. This time, however, 70 Pueblo warriors and 400 family members within the town opposed his entry. De Vargas and his forces staged a quick and bloody recapture that concluded with the surrender and execution of the 70 Pueblo warriors and with their families sentenced to ten years' servitude.

In 1696 the Indians of fourteen pueblos attempted a second organized revolt, launched with the murders of five missionaries and thirty-four settlers and using weapons the Spanish themselves had traded to the Indians over the years; de Vargas's retribution was unmerciful, thorough and prolonged. By the end of the century the last resisting Pueblo town had surrendered and the Spanish reconquest was essentially complete. Many of the Pueblos, however, fled New Mexico to join the Apache or Navajo or to attempt to re-settle on the Great Plains. One of their settlements has been found in Kansas at El Quartalejo.

While the independence of many pueblos from the Spaniards was short-lived, the Pueblo Revolt gained the Pueblo Indians a measure of freedom from future Spanish efforts to eradicate their culture and religion following the reconquest. Moreover, the Spanish issued substantial land grants to each Pueblo and appointed a public defender to protect the rights of the Indians and argue their legal cases in the Spanish courts. The Franciscan priests returning to New Mexico did not again attempt to impose a theocracy on the Pueblo who continued to practice their traditional religion.\

Following his release, Popé, along with a number of other Pueblo leaders (see list below), planned and orchestrated the Pueblo Revolt. Popé took up residence in Taos Pueblo far from the capital of Santa Fe and spent the next five years seeking support for a revolt among the 46 Pueblo towns. He gained the support of the Northern Tiwa, Tewa, Towa, Tano, and Keres-speaking Pueblos of the Rio Grande Valley. The Pecos Pueblo, 50 miles east of the Rio Grande pledged its participation in the revolt as did the Zuni and Hopi, 120 and 200 miles respectively west of the Rio Grande. The Pueblos not joining the revolt were the four southern Tiwa (Tiguex) towns near Santa Fe and the Piro Pueblos south of the principal Pueblo population centers near the present day city of Socorro. The southern Tiwa and the Piro were more thoroughly integrated into Spanish culture than the other groups. The Spanish population of about 2,400, including mixed-blood mestizos, and Indian servants and retainers, was scattered thinly throughout the region. Santa Fe was the only place that approximated being a town. The Spanish could only muster 170 men with arms. The Pueblos joining the revolt probably had 2,000 or more adult men capable of using native weapons such as the bow and arrow. It is possible that some Apache and Navajo participated in the revolt.

The Pueblo revolt was typical of millenarian movements in colonial societies. Popé promised that, once the Spanish were killed or expelled, the ancient Pueblo gods would reward them with health and prosperity. Popé's plan was that the inhabitants of each Pueblo would rise up and kill the Spanish in their area and then all would advance on Santa Fe to kill or expel all the remaining Spanish. The date set for the uprising was August 11, 1680. Popé dispatched runners to all the Pueblos carrying knotted cords. Each morning the Pueblo leadership was to untie one knot from the cord, and when the last knot was untied, that would be the signal for them to rise against the Spaniards in unison. On August 9, however, the Spaniards were warned of the impending revolt by southern Tiwa leaders and they captured two Tesuque Pueblo youths entrusted with carrying the message to the pueblos. They were tortured to make them reveal the significance of the knotted cord.

Taos Pueblo served as a base for Popé during the revolt.

Popé then ordered the revolt to begin a day early. The Hopi pueblos located on the remote Hopi Mesas of Arizona did not receive the advanced notice for the beginning of the revolt and followed the schedule for the revolt. On August 10, the Puebloans rose up, stole the Spaniards' horses to prevent them from fleeing, sealed off roads leading to Santa Fe, and pillaged Spanish settlements. A total of 400 people were killed, including men, women, children, and 21 of the 33 Franciscan missionaries in New Mexico. Survivors fled to Santa Fe and Isleta Pueblo, 10 miles south of Albuquerque and one of the Pueblos that did not participate in the rebellion. By August 13, all the Spanish settlements in New Mexico had been destroyed and Santa Fe was besieged. The Puebloans surrounded the city and cut off its water supply. In desperation, on August 21, New Mexico Governor Antonio de Otermín, barricaded in the Palace of the Governors, sallied outside the palace with all of his available men and forced the Puebloans to retreat with heavy losses. He then led the Spaniards out of the city and retreated southward along the Rio Grande, headed for El Paso del Norte. The Puebloans shadowed the Spaniards but did not attack. The Spaniards who had taken refuge in Isleta had also retreated southward on August 15, and on September 6 the two groups of survivors, numbering 1,946, met at Socorro. About 500 of the survivors were Indian slaves. They were escorted to El Paso by a Spanish supply train. The Puebloans did not block their passage out of New Mexico.

The retreat of the Spaniards left New Mexico in the power of the Puebloans. Popé was a mysterious figure in the history of the southwest as there are many tales among the Puebloans of what happened to him after the revolt. Later testimony to the Spanish by Pueblo Indians was probably colored by anti-Popé sentiments and a desire to tell the Spanish what they wanted to hear.

Apparently, Popé and his two lieutenants, Alonso Catiti from Santo Domingo and Luis Tupatu from Picuris, traveled from town to town ordering a return "to the state of their antiquity." All crosses, churches, and Christian images were to be destroyed. The people were ordered to cleanse themselves in ritual baths, to use their Puebloan names, and to destroy all vestiges of the Roman Catholic religion and Spanish culture, including Spanish livestock and fruit trees.[17] Popé, it was said, forbade the planting of wheat and barley and commanded those Indians who had been married according to the rites of the Catholic Church to dismiss their wives and to take others after the old native tradition.

The Puebloans had no tradition of political unity. Popé was a man of trust and strict policy. Therefore, each pueblo was self-governing, and some, or all, apparently resisted Popé's demands for a return to a pre-Spanish existence. The paradise Popé had promised when the Spanish were expelled did not materialize. A drought continued, destroying Puebloan crops, and the raids by Apache and Navajo increased. Initially, however, the Puebloans were united in their objective of preventing a return of the Spanish.

Popé was deposed as the leader of the Puebloans about a year after the revolt and disappears from history. He is believed to have died shortly before the Spanish reconquest in 1692.

Spanish attempt to return

Little is known about Po’pay prior to his arrest in 1675. It is estimated that he was born in 1630, which means he came of age during a period of enormous strife and hardship. Famine and attacks were decimating the pueblos. The Spanish were unable to protect them and, instead, were aggressively eradicating their way of life. Po’pay was described as a “fierce and dynamic individual…who inspired respect bordering on fear in those who dealt with him.”

After his release from prison, Po'pay retreated to Taos Pueblo, the northernmost outpost of the Spanish Empire. The residents of Taos had a reputation for aggressively resisting the Spanish. Po’pay began to organize and plan the rebellion. His objectives were focused and clear: drive the Spanish from ancestral land, eradicate their influence and return to the traditional ways of life. He began secret negotiations with leaders from all other pueblos. The extent of the animosity towards the Spanish is reflected in the fact that Po’pay was able to travel to over 45 pueblo towns over a 5-year period of time, meeting with the leaders of each community, without the Spanish finding out. Even the Apache and Navajo, who were traditionally perceived as enemies, participated, though little is known about their level of involvement in pre-revolt planning. Po'pay was so committed to the revolution that he murdered his son-in-law, Nicolas Bua, based on fears that he would betray the plot to the Spanish.

He gained the support of the Northern Tiwa, Tewa, Towa, Tano and Keres-speaking Pueblos of the Rio Grande Valley. Pecos Pueblo, 50 miles east of the Rio Grande, pledged its participation in the revolt, as did the Zuni and Hopi, 120 and 200 miles west of the Rio Grande respectively. The Pueblos not joining the revolt were the four southern Tiwa (Tiguex) towns near Santa Fe and the Piro Pueblos near present day Socorro. The southern Tiwa and the Piro were more thoroughly assimilated into Spanish culture than the other communities. Po’pay couldn’t risk confiding in them due to concerns about their allegiance to the Spaniards.

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, there was no precedent for political unity among the pueblos. They were separated by distance, culture and language, interacting to trade, but otherwise maintaining their independence and autonomy. Inadvertently the Spaniards had provided the key element necessary for cooperative action…a common language. By 1680 all of the pueblos spoke Spanish.

From his base of operations at Taos Pueblo, Po’pay and his confederates laid out their plan and coordinated their attack. The date set for the uprising was August 11, 1680. Runners were dispatched to all the Pueblos carrying knotted cords. Each morning the Pueblo leadership was to untie one knot from the cord, and when the last knot was untied, that would be the signal for them to rise against the Spaniards in unison. Each Pueblo was to raze its mission church, then kill the resident priest and neighboring Spanish settlers. Once the outlying Spanish settlements were destroyed, the Pueblo forces would converge on the capital to kill or expel the remaining Spanish.

On August 9, 1680 the Spanish were warned about the impending revolt by southern Tiwa leaders and intercepted two of the runners. The runners were tortured until they revealed the significance of the knotted cord. The Spanish population of about 2,400, including mixed-blood mestizos, and Indian servants and retainers, was scattered throughout the provinces. Santa Fe was the only significant town, with a mere 170 soldiers available for defense.

When the Pueblo leaders found out that the runners had been captured and their plan had been compromised, they decided to start the revolt a day earlier. Runners were sent out with new instructions that the uprising would commence the morning of August 10th. Due to the vast distance between Taos and the western pueblos of the Acoma, Zuni and Hopi, those communities didn’t get the memo regarding changes. They followed the original timeline.

On August 10, 1680, Tewa, Tiwa, and other Keresan-speaking pueblos, and even the non-pueblo Apaches simultaneously rose up against the Spanish. The Zuni, Hopi and Acoma were a day late. In Santa Fe, Governor Otermin marshaled the city's resources to defend the capital. By August 13, all the Spanish settlements in New Mexico had been destroyed and Santa Fe was under siege. Otermin began sending out heavily armed relief parties to escort stranded colonists to the relative safety of Santa Fe. By August 15 almost 1000 people were crowded in the Governor’s Palace, surrounded by an army of 2500 Indian warriors, with no water and limited food. In the meantime, over 1000 additional survivors from the Rio Abajo, under the command of Lt. Governor Alonso Garcia, had gathered in Isleta, 70 miles south of Santa Fe. Neither group was aware of the other.

On August 21 the Spanish broke out of the Governor’s Palace, launching a costly counter attack to drive the warriors from the city, allowing the refugees time to flee. They began the long trek south. The refugees in Isleta were also heading south when they got word about the other survivors. They paused in Socorro, waiting for the refugees from Santa Fe to arrive and then traveling together on September 27th to El Paso. The Puebloan warriors shadowed them the entire way, essentially escorting them to the border, but they didn’t attack. The goal was not wholesale slaughter, because it would have been easy to eradicate the remaining Spanish as they traveled south. The goal was expulsion; a violent rejection of Spanish oppression. The revolt cost 400 Spanish lives, including 21 of the 33 priests in New Mexico; however, 2000 Spaniards survived.

After the revolt Po'pay became the leader of the Pueblo Alliance for a brief period of time. Popé and his two lieutenants, Alonso Catiti from Santo Domingo and Luis Tupatu from Picuris, traveled from town to town ordering a return "to the state of their antiquity." All crosses, churches, and Christian images were to be destroyed. The kivas were restored. The people were ordered to cleanse themselves in ritual baths, to use their Pueblo names, and to destroy all vestiges of the Roman Catholic religion and Spanish culture, including Spanish livestock and fruit trees. Popé, it was said, forbade the planting of wheat and barley and commanded those married in the Catholic church to dismiss their wives and to take others based on native traditions.

Many of the pueblos, unaccustomed to cooperative political action, and accustomed to autonomy, ignored his orders. His effort to rule all the Pueblos was resented and he was considered a tyrant by many. Additionally, there were Puebloans who had become sincere Christians, with ties of family and friendship with the Spanish.

Po’pay was deposed as the leader of the Pueblos about a year after the revolt, though he was reelected in 1688, shortly before his death. After his death the de facto confederation of the pueblos fell apart. Opposition to Spanish rule had given the Pueblos the incentive to unite, but not the means to remain united once their common enemy was vanquished.

For 12 years, the Pueblos prevented the Spanish from returning, successfully repelling attempts in 1681 and 1687. However, the prosperity Po’pay had promised didn’t materialize. Expulsion of the Spanish forces did nothing to end the drought. Ongoing crop failure and famine, absent the Spanish military presence, led to increasingly frequent and aggressive attacks by Apache, Navajo, Comanche and Ute raiding parties. Furthermore, eradicating all traces of Spanish colonialism proved to be more challenging than anticipated. Many Spanish commodities, like iron tools, sheep, cattle, and fruit trees, had become an integral part of Pueblo life. A few individuals, influenced by the teachings of the Franciscans, rescued and hid the sacred objects of their adopted religion, awaiting the eventual return of the Spanish friars.

In 1692 Diego de Vargas Zapata y Luján Ponce de Leó launched a successful military and political campaign to reclaim the territory. In August 1692, Vargas marched to Santa Fe unopposed. He stopped in Pecos Pueblo expecting a battle and was surprised to be warmly received. Pecos provided 140 additional warriors to help him retake Santa Fe. He was accompanied by a converted Zia war captain, Bartolomé de Ojeda, 60 Spanish soldiers, 100 Indian auxiliaries, 7 cannons and 1 Franciscan priest. They arrived in Santa Fe on September 13 where he met with 1000 Puebloans, promising clemency and protection if they would swear an oath of allegiance to the King of Spain and return to the Christian faith. They didn’t go for it right away. Vargas had to negotiate for several days, but after enduring a decade of endless raids, the Spanish were no longer viewed as the worst enemy. The Spanish finally wrangled a peace treaty. On September 14, 1692 Vargas proclaimed a formal act of repossession. Over the following month he visited other Pueblos, forcing acquiescence to Spanish rule, sometimes encountering resistance, often receiving a warm reception.

Though the 1692 peace accord was achieved relatively peacefully, it did not lead to a full restoration of Spanish authority, due in part to changes in Spanish attitudes and policy. New Mexico was no longer perceived as mission country, but as a buffer zone, protecting the precious silver mines in the south from the French and British who were rapidly advancing their colonial footprint in the Mississippi valley. The inhabitants of New Mexico were seen as potential allies in the game of transcontinental empire building, with each of the Euopean powers vying to claim as much of the continent as possible. This resulted in a different approach. The native population was to be courted rather than conquered. The zealotry of 17th century Franciscan “Conquistadors of the Spirit” approach abated.

However, that doesn’t mean there was no further conflict. Vargas exerted increasingly severe control in the 1690s, again provoking ambivalence and open defiance. When Vargas returned to Mexico in 1693 to gather additional colonists and troops, he returned to Santa Fe to find 70 Pueblo warriors and 400 of their family members opposing his entry. He ordered his troops to attack, resulting in a quick, bloody recapture. The 70 warriors were executed and their families were sentenced to 10 years of slavery.

In 1696 the Indians of 14 pueblos attempted a second organized revolt, launched with the murders of 5 missionaries and 34 settlers, using weapons procured from the Spanish. Vargas' retribution was prolonged and unmerciful. By the end of the 1600s he secured the surrender of the last Pueblo town in the region. Many Puebloans fled, joining Apache or Navajo groups. Some of the pueblos were never convinced to rejoin the Spanish Empire and were far enough away to make attempts at re-conquest impractical. For example, the Hopi remained free of any Spanish attempt at re-conquest; though the Spanish did launch several unsuccessful attempts to secure a peace treaty or a trade deal. In that regard, for some pueblos, the Revolt successfully diminished the European influence on their way of life.

The 1680 uprising was not an isolated event. The 17th century was punctuated by unrest and rebellion. Many of the region’s people had been conquered and abused, but they understood that despite greater numbers, their foe was ruthless, organized, and well-armed. The Spanish possessed firearms and steel weapons superior to anything the Natives could muster. But despite the odds against successful resistance, Spanish records reflect a pattern of persistent plots and rebellion among native tribes who supposedly had been “reduced” to Christianity and Spanish ways

.

While the independence of many pueblos from the Spaniards was short-lived, the Pueblo Revolt gained the Pueblo Indians a measure of freedom from future Spanish efforts to eradicate their culture and religion. Both the Spanish and the Pueblos were decimated by the revolt and its aftermath. The Spanish adapted their outlook and policies, which may have spared additional atrocities as they expanded their empire west into California. Forced labor and tributes were prohibited in New Mexico. Furthermore, the Spanish issued substantial land grants to each Pueblo and appointed a public defender to protect the rights of the Indians and argue their legal cases in the Spanish courts. The Franciscan priests returning to New Mexico altered their approach as well, becoming more tolerant of indigenous religious expression. Pueblo warriors and Spanish soldiers became allies in the fight against their common enemies; the Apaches, Navajo, Utes, and Comanche. Over the centuries of conflict and cooperation, New Mexico became a blend of all of these cultures.

CONCHA

Fifteen-year-old Alonso Concha was cold and hungry. As he stood closer to the horno, the traditional Pueblo outdoor oven, his thoughts turned to his older brother, Arcenio who had gone south toward Santa Fe several months ago ostensibly to find work. Concha knew better. It was November 1675 according the hated Spaniard’s calendar. Drought, poor crop yields, Spanish plundering and Catholic Franciscan Friar’s corruption had left the people of the Taos Pueblo starving, poor and angry. His brother no doubt was not looking for work, but instead a little adventure and escape from their dreary existence. Concha himself might have gone too, but someone needed to remain with their mother and also care for Eah Walla, his aged grandfather because his father had died a year ago from a wasting disease, no doubt carried by their Spanish conquerors. The other thing that held him back was himself, for unlike his brother, Concha was no fighter. Slight of build, he knew that even when he got older, he would not be as strong and able as his elder brother.

--excerpt from the historic fiction novella included in the books noted below along with several other stories of the Southwest.

---------------------------------------------------------

Set amidst the true story of the revolt in Taos, New Mexico in 1680, a young man of the Pueblo, counseled by his grandfather,

Eah Walla must decide what a man should do.

A READER'S REVIEW -

Last night I finished Taos Uprising, a collaboration by our John Green and Eddie Hartshorn. Though stories of the old west, these aren't your stereotypical shoot-em-up cowboy stories. The first story “Taos Uprising” is a fictionalized account of the revolt of Pueblo Indians against the Spanish in the late 17th century and is rich in detail and filled with plenty of family and community drama. The attack itself is well-written and fun to read (if you like this sort of thing). The middle story, “The Last Gunfight in Ash Fork” by John Green is the passing on of that story from one generation to the next and told with such deftness it's like hearing the story being told. The final story “The Stranger” by Eddie Hartshorn is novella-length and draws a picture of a western town visited by a stranger who is never named, but by the end of this morality tale he learns as much about himself as we do about life in the old west. What makes this book also worthy of being placed in the reference section of your book shelves, is that it contains an appendix with a history of the Pueblo revolt and a history of Ash Fork, Arizona. There are pictures and drawings included on some of the pages that helps bring the stories to life.

-- Steve Carr

![]()

![]()

![]()